Mary Herbert

works exhibitions news about

Careful not to fill an Emptiness

May 15 - June 28, 2025

223 Cambridge Heath Road

London E2 0EL

exhibition text

The experience of the body can’t be measured in feet or by the length of its limbs. But as a changing and curious instrument, the body knows space as something foreclosing – an abrupt cul-de-sac in a dream – and sometimes so blown open it can feel like sensory deprivation, extending past any textured surface or distance in time.

The artworks in Careful not to fill an Emptiness move into spaces which have held – and been held by – the body. Here, these spaces are loosely described by paint or in dry materials on paper. They are shared and solitary at once: a group of figures stand together with their heads bowed, someone holds out a flower to another who is angled away and appears not to see them but is still supported by bodies on either side.

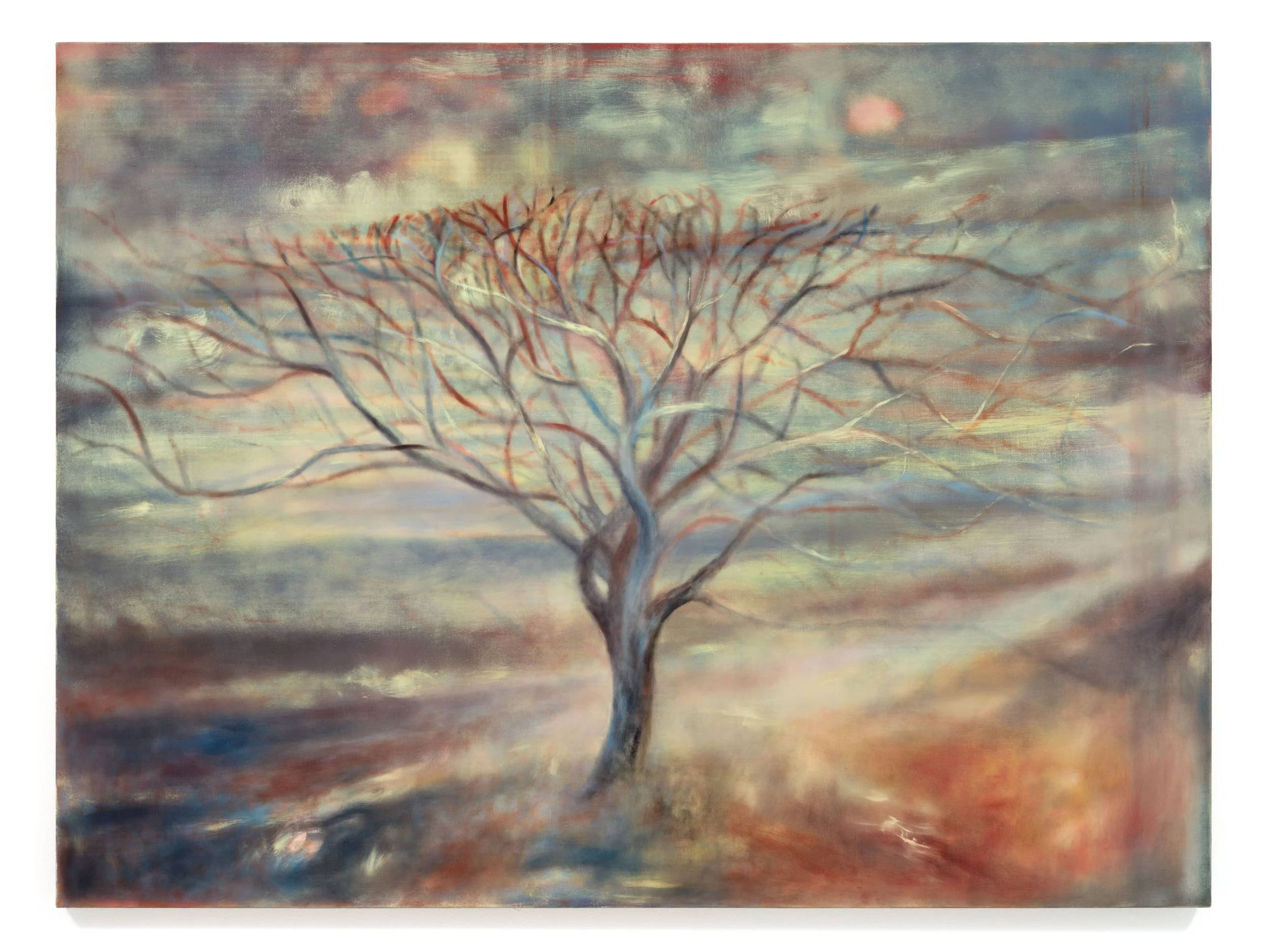

When an object or body is depicted, a surrounding space forms by default. Around the bodies of natural elements, Mary Herbert paints a kind of default landscape that doesn’t need to be clearly defined to be occupied. It is a not-quite place that exists despite the body’s vulnerability.

Although this place isn’t quite real or definite, we still recognise it: it is a rapidly changing space, accruing shared bodily actions, marked by structures of financialization, platform capitalism and social reproduction. We know something, even if we try not to, of those ways in which the body of the global majority is being excluded and exposed.

In these paintings, the body knows its vulnerability in a new way, like the body of a tree hosting life in its trunk. As though recognising this, there are places in which Herbert’s paintings and works on paper appear to cut off and away from something, holding and then breaking a temporal pact. But there is an insistence that feels bodily. She stays with the coordinates of the painted place, willing into being a space in time.

A prism is an instrument moved through by light: the body is a prism moved through by spaces, ones it has occupied and ones it hasn’t, at least not physically. As they travel in and out of the body, the body itself travels, day by day, through those spaces, forming a mobius strip of inversions. As an external plane, a painting or drawing seems to refuse space – a flat barrier against a wall – yet the expansiveness of space has been one of the core convictions of painting because of the unbounded body and its role in making an image with paint.

Within this body of work you stand before a compression of colour, its low fidelity testing what you hold onto when you move further away. This is the clarity you come closer to when you loosen the body’s grip. What does it feel like to stand in a place that will be there after your body, everybody, has gone?

There is an unwillingness to state an answer but a resistance to leaving. There is a tug backwards as the paintings push forwards into the space they occupy. You construct an experience, by default, through a combination of handling and material. This is as true in life as in painting.

Text by Aisha Farr