Imperfect Crystal

July 9 - August 13, 2022

Opening Reception: Saturday, July 9, 6-9pm

press release

Moskowitz Bayse is pleased to present Imperfect Crystal, an exhibition with works by Ilit Azoulay, Joe Biel, Charlie Goering, Anthony Miserendino, Joel Otterson, Cameron Spratley, and B. Thom Stevenson. The exhibition will be on view at the gallery from July 9 – August 13, 2022. We will host an opening reception on Saturday, July 9 from 6-9pm.

“There's a wonderful sign hanging in a Toronto junkyard which reads, 'Help Beautify Junkyards. Throw Something Lovely Away Today.' This is a very effective way of getting people to notice a lot of things.” – Marshall McLuhan

Forgotten images and objects have ways of reaching us in incomplete states, laden with degraded facts, and out of step with their earlier selves, they yearn for resurrection from the consciousness graveyard. That scattered heap becomes its own metastatic archive, as the casted-off finds a worthy partner in the artist, magnetized by that essential willingness to reuse and reanimate visual scraps and orphaned information. Scavenged information becomes the charge of the rescuer, and fresh readings are applied accordingly. Imperfect Crystal brings together artists who consider these dimmed source signals, documents, and veins of mottled intentionality and refracted history. Through material transformation, images and objects return to us, their original meanings both fortified and acutely altered.

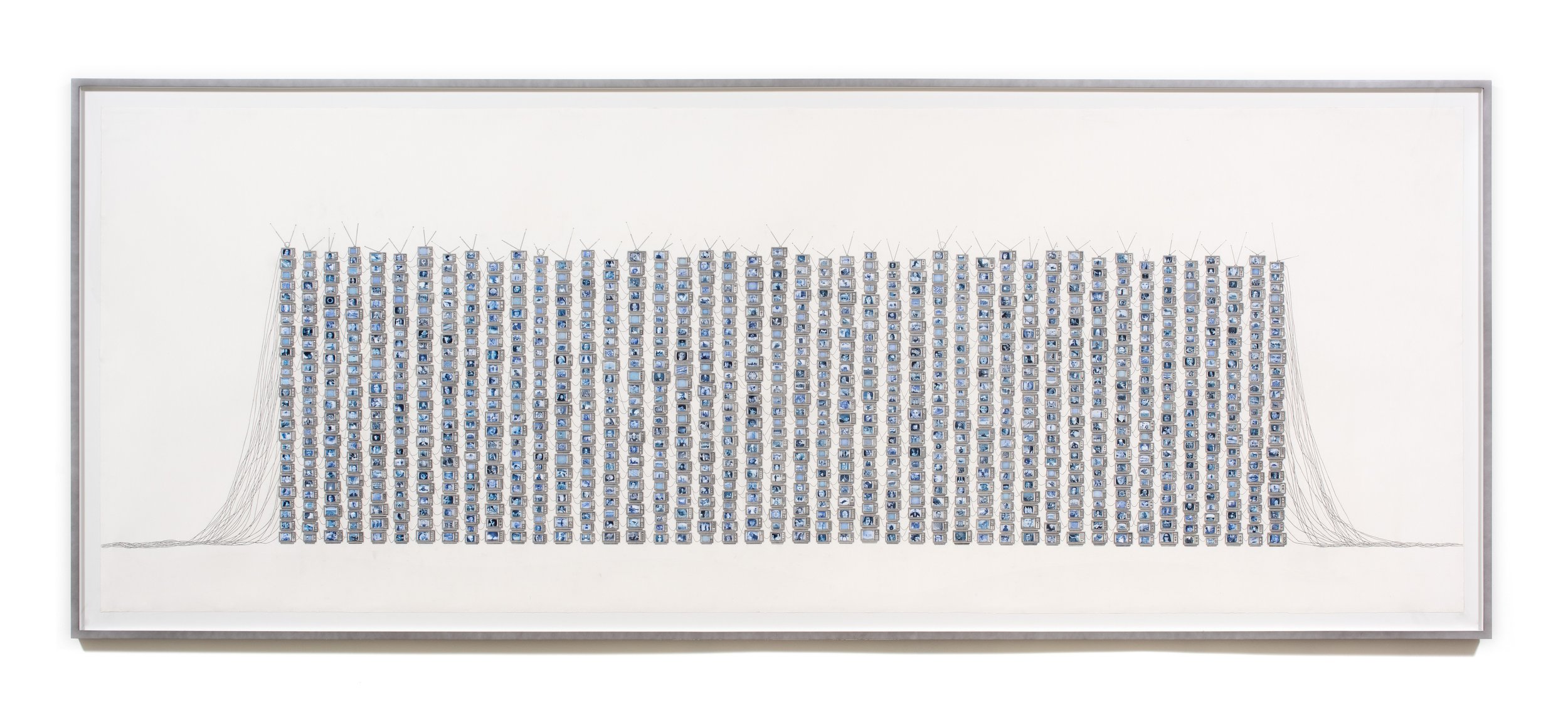

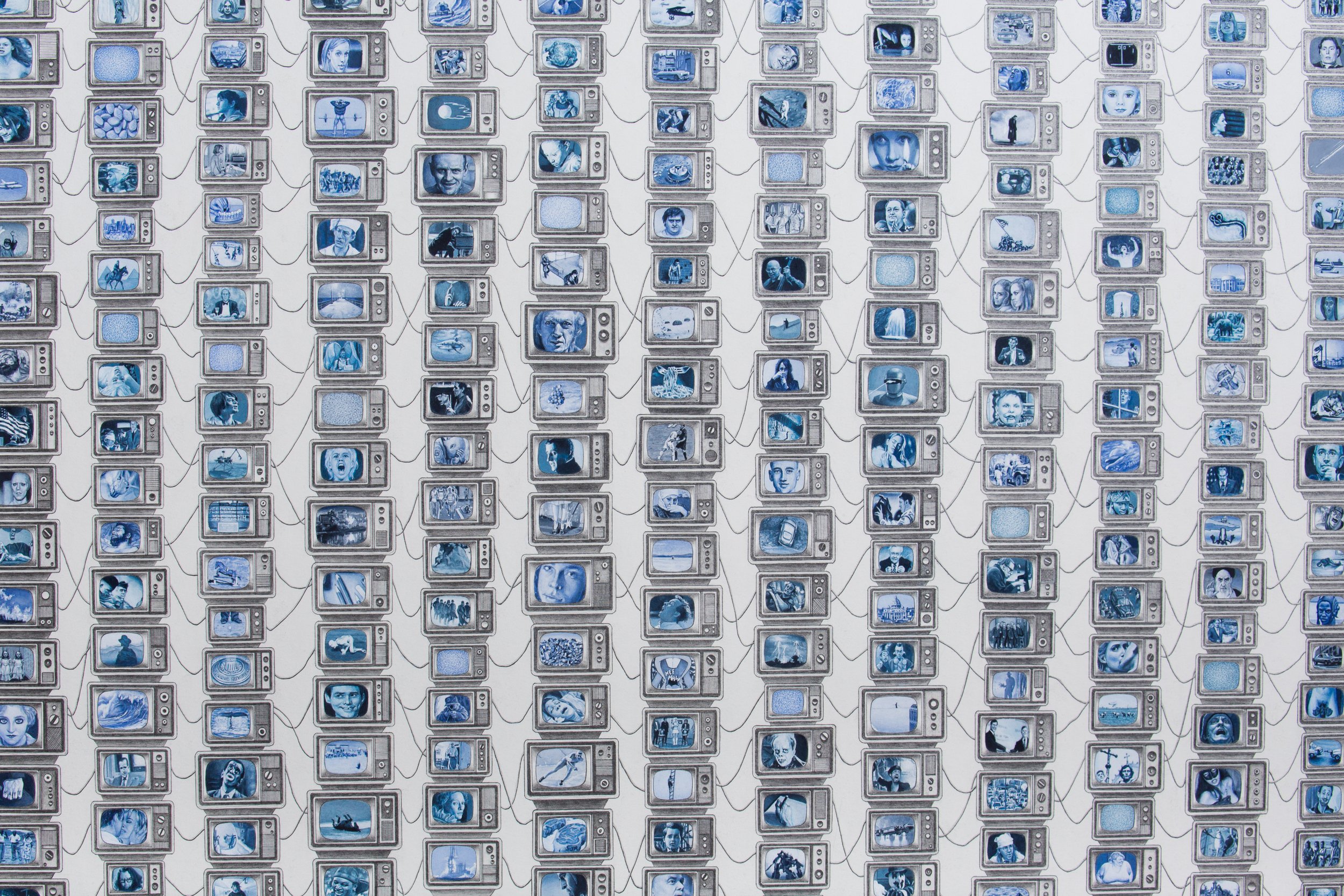

With his monumental accounting of the rise and rapidly scattered positions of the moving image, Joe Biel offers a slice of our expanded moment’s collective brain. Graphite television sets flicker with hundreds of tiny gouache images at once – some iconic, some arcane and obscure – the stacks of glowing screens that make up Veil allude to the moral proffers and practical misuses of mass-media during the dawning of the culture industry. As the medium of television slides slowly into history, the content it has dependably transmitted desperately clings to our memories. Biel, through a deeply researched digestion, arrives at that numbly impersonal self-portrait: the harrowed, overloaded reflection when the TV is finally switched off. A meta-narrative about the act of seeing and absorbing image and information, Veil stands as a testament to the specific infinitude that the television and its descendants offer: endless content for the willing, and a steady stream of infiltrative static for everyone else.

Joel Otterson looks toward more personal and bodily annals for his Flesh Cups, hand-blown vessels painted with Russian prison tattoos. The glass forms, emblematic of a mostly bygone American fetish for the trappings of European high society, become fragile bodies themselves. Formally, the tattoos reference time, religion, and, backwardly, the liberated female body and spirit. Untethered from their intended bodies, the symbols act as ghost-talismans: imagery unbound to flesh, preserved for posterity, their original bearers lost forever. The disembodied images cling to their new supports, which prove more fragile and more equipped for survival than their once-living counterparts. Otterson sets the Flesh Cups in tableaux with a gilded bronze and gemstone mounted ceramic work “Tobacco Road”, which throws name and final scene of the titular 1941 John Ford film but referencing French ormolu mounted Song Dynasty ceramics, two cultures colliding to make an object whose success lies precisely in its precarious dissonance. Like Biel, Otterson’s personally forged connections across media rely on open-sourced readings that confirm content’s adaptability to alter itself as well as its ability to convey particulars.

Also utilizing historic symbols and relics of institutionalization and marginalization, Ilit Azoulay’s Mousework series contends with antiquated approaches to the now-outmoded diagnosis of female hysteria. Beginning with the photographic archives of Jean-Martin Charcot, the ethically fraught but pioneering neurologist and medical photographer, Azoulay considers his clinic’s staged and manipulated compendium of portraits of so-called hysterical women. Set in ovular, locket-like windows on the left-hand side of a seemingly foldout frame, the historical material is paired with a photographed found object on the right, and a digitally stitched collage of Shutterstock images in the work’s center. During her research for Mouseworks, Azoulay identified the primary licensers of photographs tagged “hysteria” in Shutterstock’s offerings as pharmaceutical companies themselves, for use in new anti-anxiety and anti-depressant advertisements. Revealing the camera’s continuing complicity in defining the aesthetics of medical stigmatization, Azoulay’s Mouseworks identify fluid attitudes through associative and loaded imagery, tracing a specific and wooly historical arc towards our own moment.

In contrast to Otterson and Azoulay’s archival streamlining, Cameron Spratley seeks out images of cartoonish violence–supposed and actual–from across the vast landscape of late-analog media. Gathering screws, chains, confederate switchblade knives, Ice-T, bullet holes, porno cops, a Christ tattoo, and an asthmatic youth, the artist prints and pastes his blown-up findings to canvasses streaked by painted barbed wire, tribal tattoos, and ominous directives and missives. Spratley’s pictures engulf the viewer in thicketed fields of racialized paranoia; humor seeps through like acid where machismo and fear size one another up before finally striking an uneasy alliance. Spratley’s violence is both ghoulish and goofy, cast as definitive and bluntly parodic, abstracted, and ultimately solemnified.

Anthony Miserendino’s Splashed presents a warped collection of anonymous, implicitly personal studio wares and supplies. Cast in white gypsum cement, the artwork suggests an endless potential for malleability–a deliberate station on the road to abstraction and formal dissolution. Miserendino’s prosaic objects become seductively alien, removed just so from their logical behaviors. The viewer might seek to unfurl Splashed, countering Miserendino’s dislocation of familiarity, only to find the new objects – like ancient statuary with its missing parts and degraded passages–challenging to mentally reconstruct. Splashed, consuming its constituent source-objects, takes a knowingly obliterative position: the warped object replaces its original counterpart, momentarily, infinitely.

This denaturing of a source’s original usefulness, seen across Imperfect Crystal, is perhaps deployed most directly in Charlie Goering’s classically inflected still life paintings. Making use of objects salvaged from thrift stores and junk bins, Goering’s source objects, once imbued with (one hopes) some measure of personal significance, become abstracted in anonymity. Like Miserendino’s Splashed, Goering’s still lifes project a hermeticism and stillness, as if to assert themselves as documents of objects that are themselves victims of time and neglect, whose usefulness was never completely understood to begin with. The dinner bell and knife shed their old selves, becoming opposites and echoes of one another, containers of blunted memories.

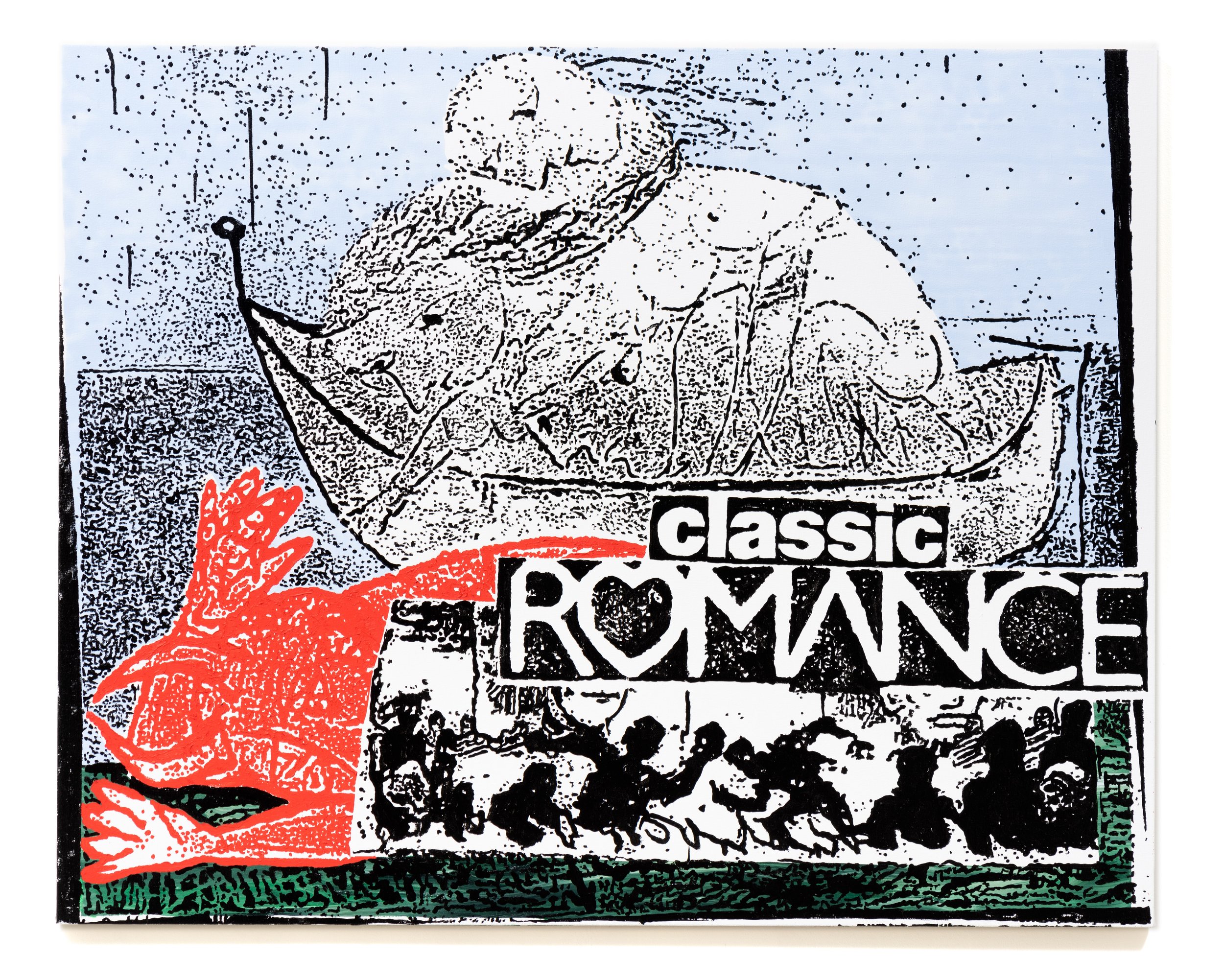

Melding Goering and Miserendino’s love of the anonymously singular object with Spratley and Biel’s fascination with the image’s infinite degrees of recognizability, B. Thom Stevenson incorporates a Picasso etching, a sci-fi pulp magazine, an art history textbook, and an anarcho-surrealist underground publication in his painting Classic Romance. With the Xerox grain faithfully translated in paint, the images coalesce under that genre-defining technology’s lo-fi umbrella of DIY crunchiness. Stevenson’s painting speaks to an eventual siloing of images, as Picasso and punk come to one day occupy the 20th century room in a future museum chronicling the entire arc of our civilization. As time progresses, the nuances of taste and subculture will collapse under the weight of capital and convenience, and vastly distinct moments and cultural narratives collide.

While only Picasso’s unmissably equine profiles stand out as broadly recognizable, Stevenson’s cut-and-paste, flattening impulse typifies the democratizing spirit that runs through the artworks and practices in Imperfect Crystal. Source imagery exists along a delicate spectrum, where association, impression, content, and context contribute to the viewer’s understanding of an artwork in necessarily uneven measures and degrees. The artist, for his or her part, collates this fractured information, assembling our shared wilderness and sprawling esoterica into legible statements of form and meaning. For the artwork to reach us, the source must reach the artist; how, when, and why that happens, it seems, is an interminably varying equation of luck and searching.