Rachael Browning

works exhibitions news about

pushing rope

February 15 - March 16, 2022

press release

Moskowitz Bayse is pleased to present Pushing Rope, an exhibition of new photographs and drawings by Rachael Browning. Pushing Rope is the artist’s second solo presentation with the gallery, and will be installed in our Viewing Room from February 15 - March 16, 2022. We will host an opening reception for the artist on Saturday, February 19 from 6-9pm.

“Foirade: disgusting? Utter nonsense! Une foirade is a lamentable failure… something one attempts that is destined to fail, but must be attempted, nonetheless, because is unquestionably worth the effort… thus, a lamentable failure.”

–Israel Horovitz, A Remembrance of Samuel Becket, 1997

Rachael Browning’s Pushing Rope is the result of a willfulness to embrace failure: une foirade. There is no ingenuity in her compositions. Attempting to push entropy beyond its limits, her work intentionally resides on the brink. The almost is overwhelmingly and intentionally present: almost perfect, almost right, almost finished, almost unachievable, almost absurd, almost a failure…

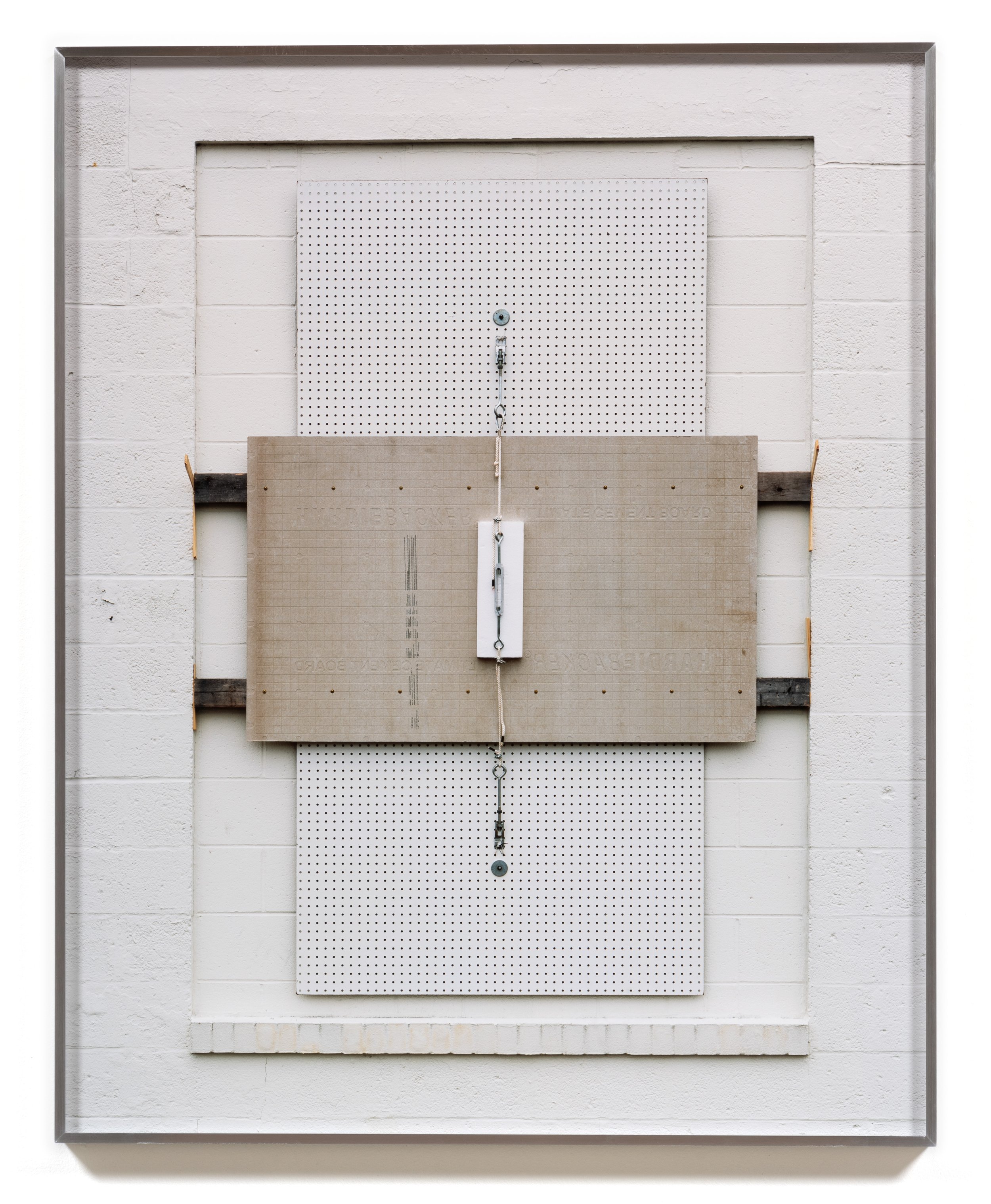

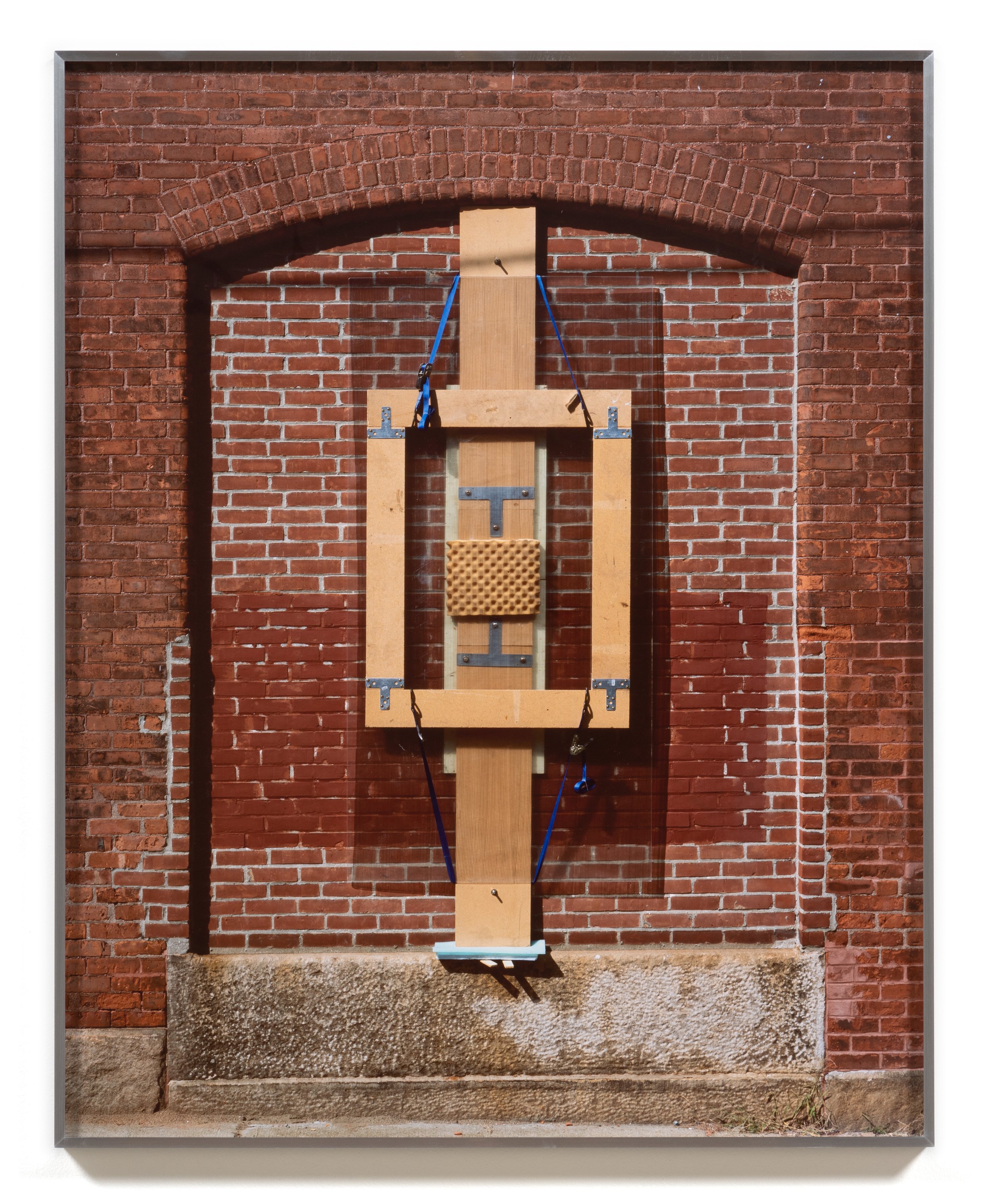

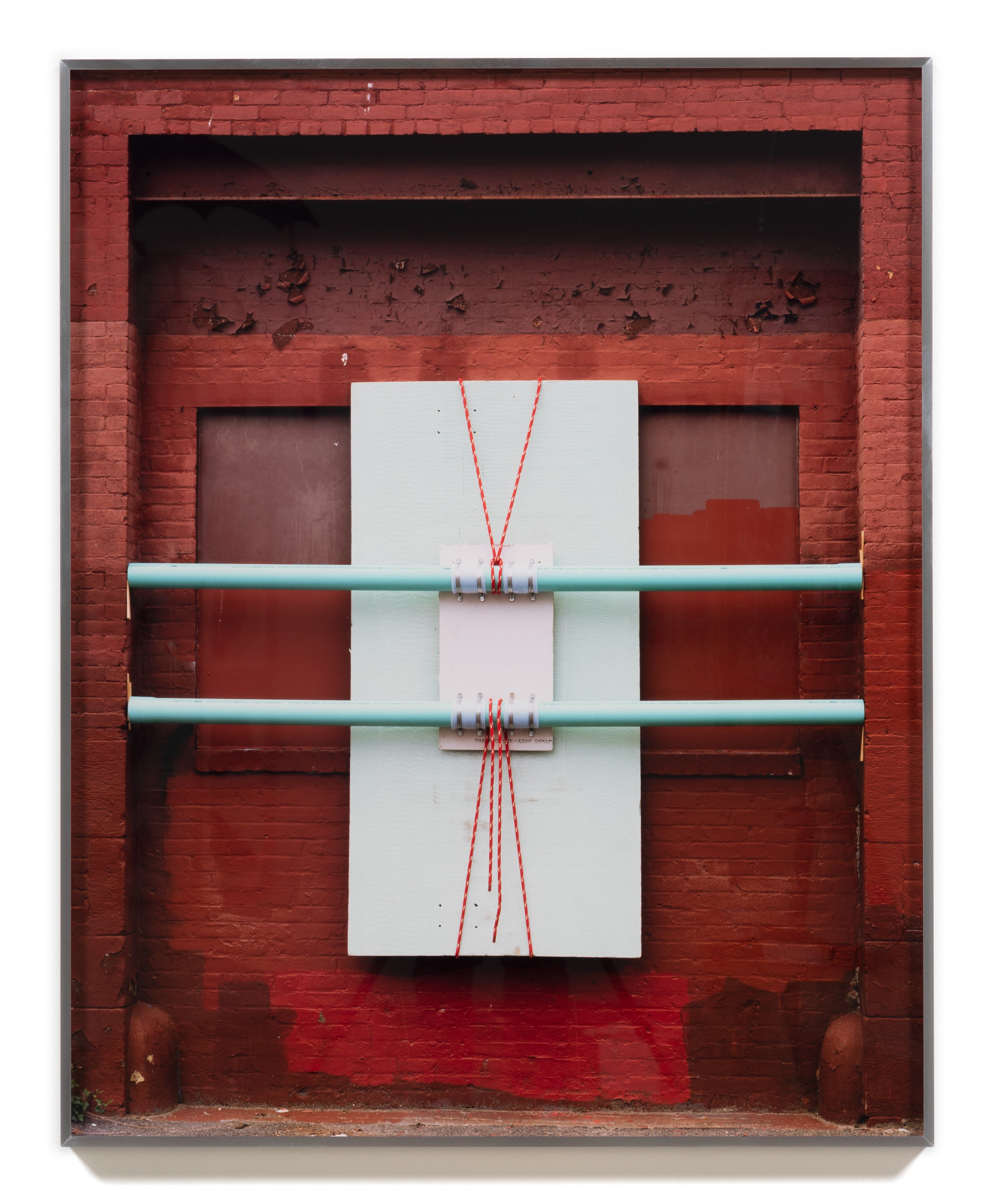

Browning’s selection of and encounter with her material is an attempt to find problems and to delineate questions in order to find solutions. In her work, the question of what failure is becomes inordinately complicated the moment one admits–if one can admit–that she has a material mastery of all those elements that shape her sculpture, become her photographic compositions, and ultimately turn into her drawings. Pushing Rope also derives from Browning’s intention to abridge the matter of perspective by forcing the flattening of three dimensions; for this reason, she sets her sculptures in blind windows that have a maximum depth of two inches.

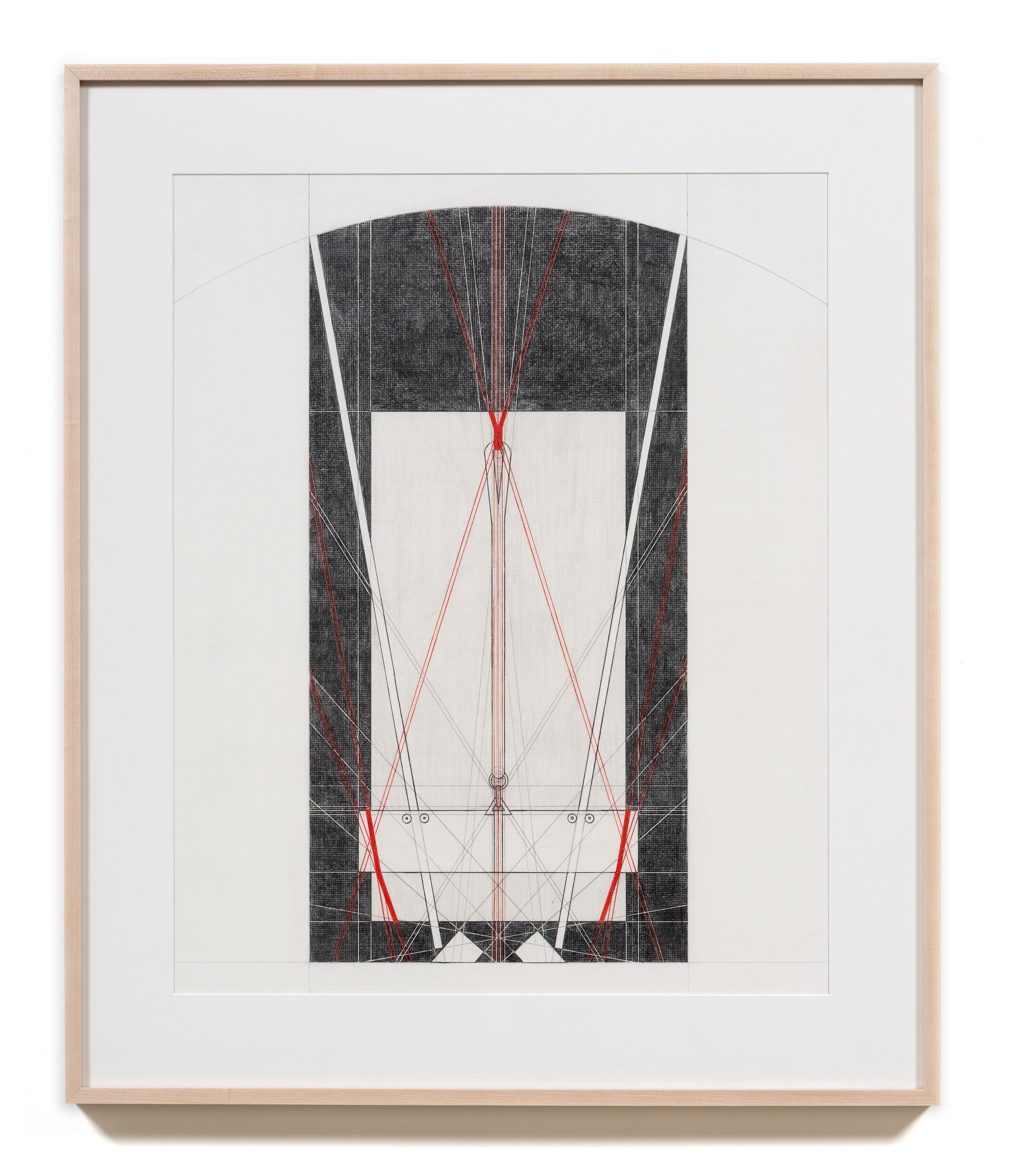

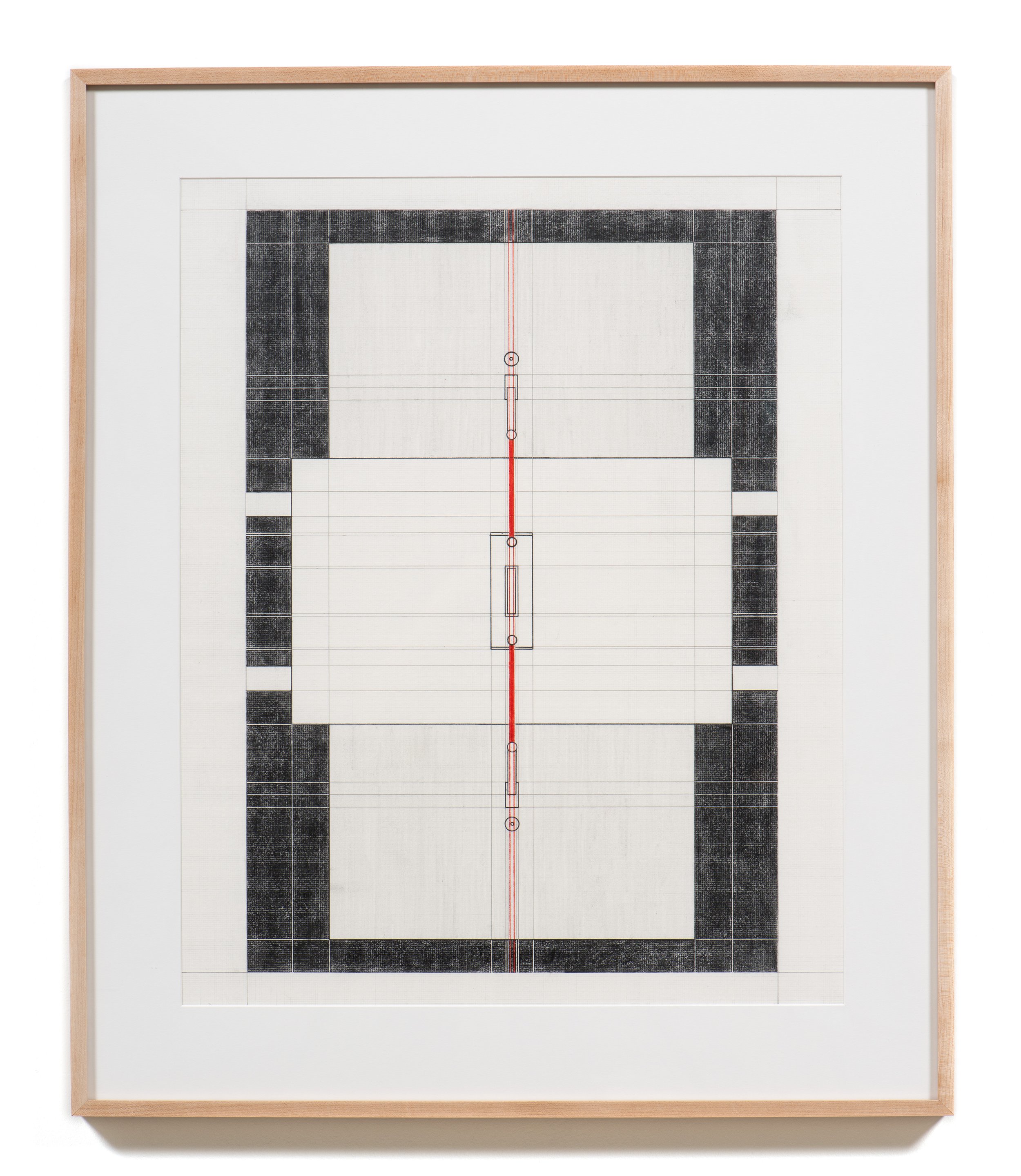

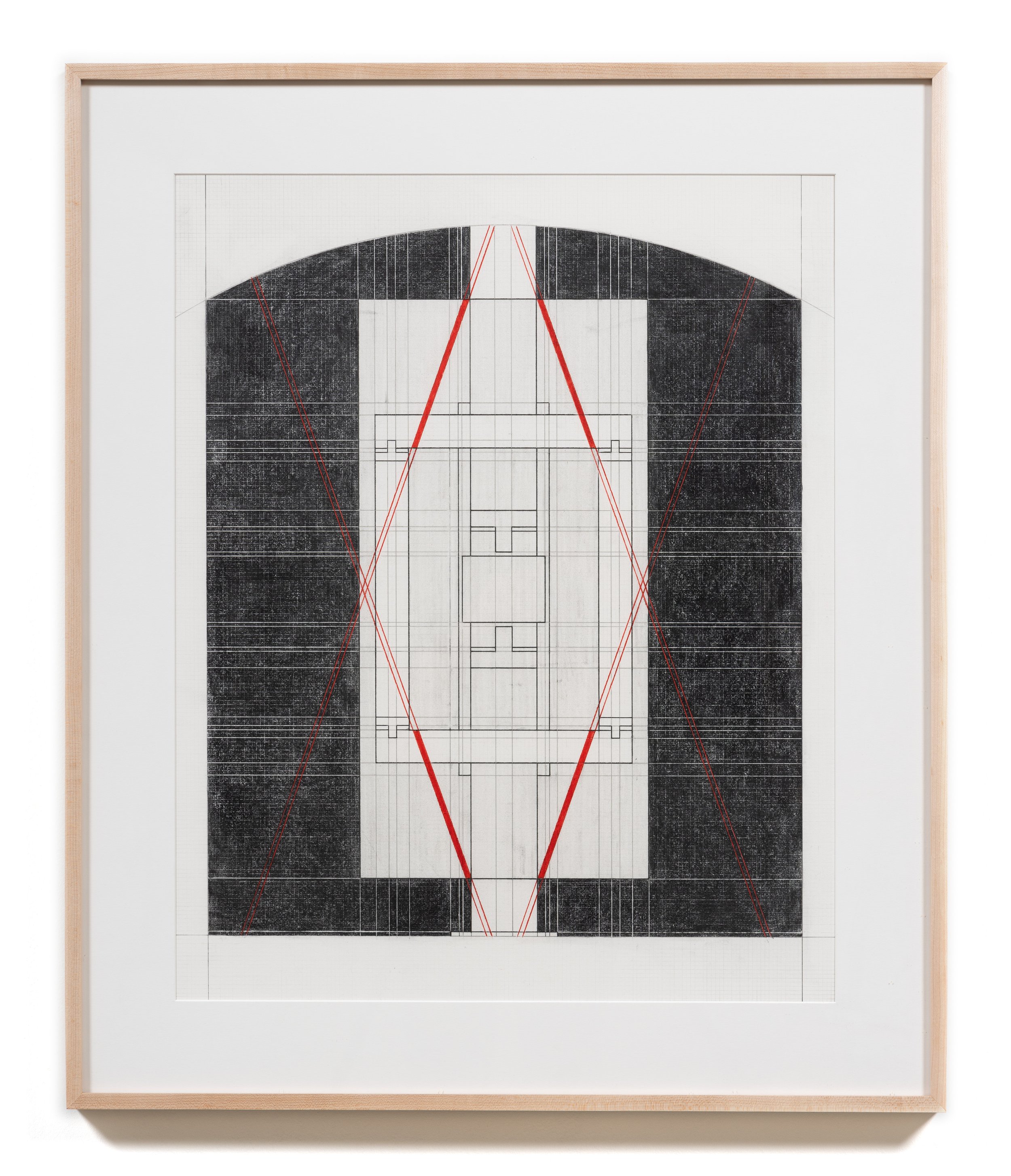

The artist subjects her sculptures, photographs, and drawings to different conditions. The sculptures’ assembly verges on achieving a two-dimensional array; they are not a reduction but a thoughtful simplification. The photographs require a certain set of lighting conditions; they are clean and simple. The drawings exist in a space of idealized abstraction; they are labored over with a degree of precision that exists conceptually everywhere but visually and structurally, only here.

Browning purposely fights against gravity and plays with entropy. The photographs and the drawings display the result of the sum of these forces. In most of the compositions, rope becomes the visual binding force that attempts to delay the failure momentum, the tendency of the elements to return to a state of disorder, to tangle, to break.

The balance between determinacy and indeterminacy creates visual and conceptual tension. The foirade of Pushing Rope is a result of Browning’s arrangement of the materials and the materials’ self-organized nature that demonstrates an art of letting go. The work inhabits the aftermath of the acts of gathering, ordering, presenting, waiting, and meditating which do not refer only to the objects, but also to scale, location, and above all, to impossibility. The impossibility here illustrates the panoply of anxiety that attends the tangle of achieving a fixed perspective and attaining control. It is Browning’s effort of holding, by virtue of its impossibility, the one that gets it right by getting something wrong.

It is not easy to categorize the artist’s work; any attempt to draw distinctions between the sculpture and the photographs quickly runs into problems. Are the materials assembled by Browning to be considered sculptures, or part of a two-dimensional image that nonetheless retains volume? A photograph is not a sculpture and the scale between the photographs and the drawings would seem arbitrary. By the simple fact of being in the same space those who come to encounter Browning’s work immediately face the question of human scale.

The artist follows the logic of how an “average man” can manipulate a standard four by eight foot sheet of material–plywood or drywall, for example. She works with the mechanics of the human body while retaining the irony of impossibility struggling with the restriction of sculpting one single human body: her own. She becomes the standard measure to solve the problem of scale, the frame, and the rope to work against gravity. All well and good, but for practical purposes, or purposes of functionality. Ironically–or not–by repurposing materials, Browning moves away from ideas of functionality, and lets the spectator encounter a moment of aesthetic displacement. She gets so close to precision, but she is generous enough to share with us the lamentable failure.

For Browning, the photographs in comparison to the drawings have a lot to say about scale: each image floats a piece of material that is the same size, but they present as different sizes in the final image. Scale is a question that is–momentarily–solved via juxtaposition. The drawings present an opportunity to pay attention to the details that might be passed over in the photographs at first sight. The temporal intervals between the sculpture, the photograph, and the drawings blur. Tactical objects like bolts, bungees, mallet ledges, metal wire, clamps, and rope are part of the partial and absurd solution. Both the images and the drawings present an absurd precision that complicates the temporality of Browning’s work. At the same time their intrinsic nature and materiality muddles the scene of scale and dimensionality.

Like Browning’s previous work, those in Pushing Rope exist as two-dimensional objects. Is this an archive? Do the images function as documents? The artist suggests no; her photographs are more than a riff, her drawings are more than a reiteration of her sculptures. The works become a call and response, pointing attention to the moment just before reaching a turning point, a limit, a failure. If we look closely, the three-dimensionality of the sculptures sticks to the photos as objects in space via light, and to the drawings via fine marks that sit both on and into the surface of the paper. Across this action and reaction in the studio, this spatial awareness becomes about the laboring body: the same hands that arrange the materials as sculpture are the same as those that translate sculptures’ composition into drawings. The photographs and the drawings are not sculptures, but they are also not not sculptures. In this relationship between media the artist has created a seemingly endless feedback loop and in it, partial solutions for temporal problems of her own invention. Together, the works slyly suggest that the artist is nearly at the end of her rope–but not quite.

– Amanda Macedo Macedo